|

CA

philosophy:

An introduction to the interactive CA experiments

|

CA

philosophy:

An introduction to the interactive CA experiments

CA

flatland

In 1884 Edwin

Abbot wrote a fascinating book, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions,

in which he describes the life of two dimensional objects (creatures) and

their perception of the third dimension. Reading the book, one could grasp

how we experience the fourth dimension.

The experiments in this page describe CA flatlanders who exist in a two

dimensional space. Despite their simple behavior, they raise important philosophical

issues which in CA-flatland seem to be uncomplicated and straight forward.

We are concerned here with concepts, e.g. mind, self, and consciousness,

and wonder whether the behavior of CA-flatlanders suggests that they might

have a self, or are conscious.

Let’s remember that attributes e.g., mind or self do not exist as such.

There is not a mind organ or an organ controlling emotion. We deduce these

concepts from the behavior which we observe in an individual. Observing

CA behavior may help us to grasp the essence of these issues, and this

insight may then ease the analysis of these concepts when applied to us.

Hans Jonas

These experiments

illustrate also concisely some profound philosophical issues raised by

Hans Jonas in his important book “The phenomenon of Life”(1).

According

to Jonas: Plants, animals and the human animal display an ascending

development of organic functions and capabilities. The emergence of

the human mind does not mark a great divide within nature but elaborates

what is prefigured throughout the life-world. The organic even in

its lowest forms prefigures mind, and the mind even on its highest

reaches remains part of the organic.

In other words, the rudiments of the human mind are inherent in simple organisms like an ameba or a paramecium. Or, concepts, like mind, self, and consciousness are applicable to all forms of life. An ameba has a self, a mind and is conscious. Obviously its mind only prefigures ours, and so are its other attributes. However understanding ameba’s mind may assist us in the understanding of our mind.

Imagine

that some brainless creatures like an ameba are conscious and may have a

mind. How does it relate to our understanding of our mind that requires

a brain to exist.

Emergence

The

CA has two genes. {initial condition , rule}, represented by two numbers

{1 , 600}. You plant a zygote or a number one, represented by a square and

it emerges into a CA. Emergence depends on the space in which CA exist.

The two genes inherited from CA to CA are the blueprint of CA life, yet

lack any information how the CA phenotype will emerge. The first experiment

displays CA with different genes (rules). The system presented here consists

of two interacting CA called proliferon

Emergence is an unpredictable process. The zygote with its two genes does

not reveal to us (observers) how it will evolve. Despite its simple structure

CA behavior is unpredictable. Its trajectory is computationally irreducible

and may be outlined only by observation. Nevertheless as a whole the proliferon

is predictable. It always approaches and settles at an end-point. It

always attempts to maximize its resources, yet the manner how it maximizes

is unpredictable. Observing its behavior we conclude, that the proliferon

“knows” something which we are unable to express mathematically. In order

to find out how the proliferon reaches its end-point we have to observe

its behavior all the way. This proliferon wisdom is called here Wisdom

of the Body (WOB) .

|

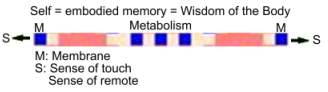

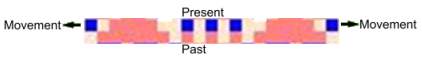

The image displays one state of an adult CA which oscillates between 46 states. The two exterior bits of a CA are its one dimensional membranes (M) which seal off the CA-self from the environment. Changes within the membrane are manifestation of CA metabolism or turnover. Each membrane bit has two sensors, one for touch and one senses remote objects.

CA-self

How do we know that a CA has a self? We don’t know. After all we don’t know whether our neighbor has a self. All we know that he is covered by a membrane, his skin, which seals off its inside, or self. The same reasoning applies to any living organism an even to a CA, which is also covered by a membrane.

Three characteristics of animal life

According to Jonas three characteristics distinguish

animal from plant life: motility, perception , and emotion (p. 99).

All three manifest a common principle. First we ought to realize that

environment and the organism are contiguous. In plants, chemicals

are directly exchanged between environment and organism. Since immediacy

of satisfaction is concurrent with the permanent organic need, in this

condition of continuous feeding there is no room for desire. Plants lack

emotions.

The animal feeds on existing life, continuously destroys its mortal supply

and has to seek elsewhere for more. There

is a “linkage between motility and emotion” (p.100).

The appearance of directed long-range motility thus signifies the

emergence of emotional life. Greed is at the bottom of chase, fear at the

bottom of flight. If appetition is the basic condition of motility, pursuit

is the primary motion. Fulfillment not yet at hand is the essential condition

of desire. Emotion implies distance between need and satisfaction.

“Emotion has no external organ by which to be identified and to force its way into a physical account” (p.100). It is embodied and cannot be localized or measured.

|

(The image depicts two CA states)

The CA senses remote objects toward which it moves. This “directed long-range motility” indicates that the CA has emotions. It’s “greed is at the bottom of chase.” The less resources it carries the faster its chase.

CA

conditioning and memory

Every live

form is equipped with an instinct of association. External stimuli

trigger processes in the organism, some are concurrent or associated. Association

may be advantageous or threatening. In either case it will be manifested

by movement, either toward, or from the stimuli. Conditioning is based

on the association instinct and requires an embodied memory. We cannot

observe the conditioning process itself. We deduce it from the behavior

of the organism (v. CA conditioning).

Proliferon

The proliferon is the minimal construct which displays some essential characteristics

of life, motility, perception and emotion. You may regard it as a byte

of a complex model simulating life. It pre-figures attributes which

will emerge in multi-proliferon systems, e.g., robots.

Modern robotics is dominated by anthropomorphism. It is led astray by false

notions that consciousness and mind are manifestations of our brain and

require a brain organ. However if you follow Jonas’ reasoning you soon realize

that even an ameba has a mind, a prefigured one which is easier to model

than our brain.

Robot domestication

Robots

cannot be designed as such, they have to be grown, like animals. You plant

two zygotes and create a proliferon. Let it interact with another one.

Add more and more proliferons, and select the set which meets your expectations.

Exactly as it is done during domestication of animals.

Additional reading:

Robot psychology

Slime

mold intelligence

Will and imagination

References

1. Hans Jonas The Phenomenon of Life- Toward a Philosophical Biology

Northwestern University Press Evanston Ill 2001